History

The Maryland Historical Society introduced its new identity as the Maryland Center for History and Culture in September 2020. Having just celebrated its 175th anniversary, the historical society’s leadership elected to rebrand the organization for the future as an inclusive “center.” The Maryland Center for History and Culture welcomes people from all walks of life to connect with the history, art, and culture of Maryland, gain new perspectives on the past, build community, explore identity, and broaden their understanding of the world.

Our Beginning

While we are excited for what the next 175 years will hold, it is important to recognize the hard work and dedication of the people who collected, donated, and preserved the vast collection of Maryland history that now lives at the Maryland Center for History and Culture.

The Maryland Historical Society was founded in 1844 when 22 men gathered in the Baltimore City post office for the purpose of collecting the “remnants of the state’s history” and preserving their heritage through research, writing, and publications. John Spear Smith was elected the historical society’s first president, and by the end of that first year, the organization had grown to 150 members.

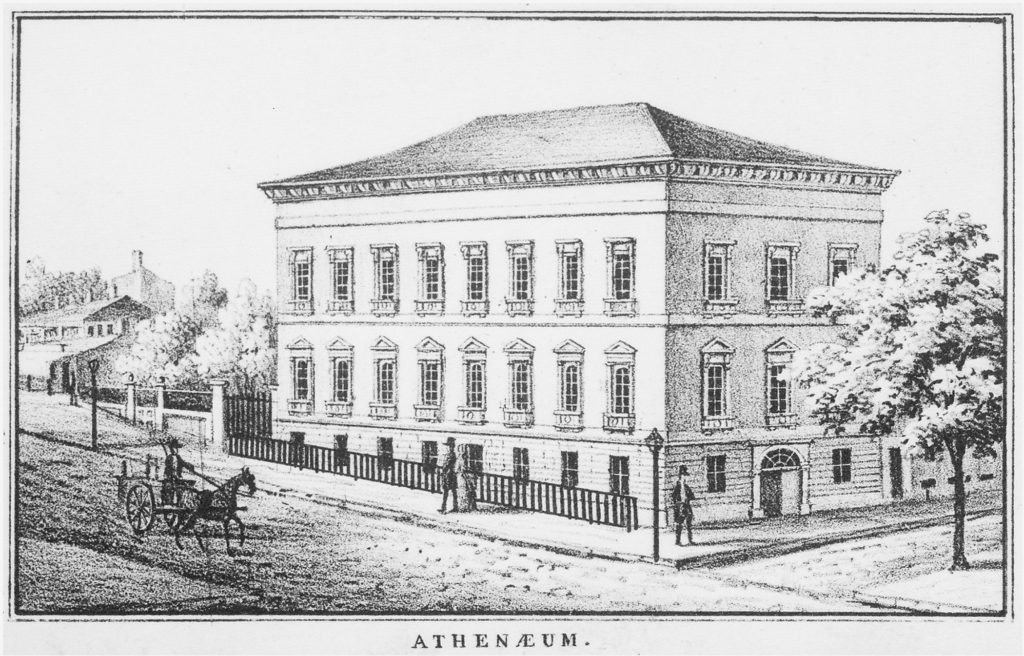

The meeting rooms at the post office could no longer accommodate so many members and a safe at the Franklin Street Bank was quickly overflowing with documents and artifacts donated to the historical society. The historical society’s members looked to one of America’s foremost architects, Robert Carey Long, to build and design their new home. The result was the Athenaeum, a four-story “Italian palazzo” building with space for an art gallery and outfitted with fireproof closets that opened in 1848.

After settling into the Athenaeum, the historical society’s membership and donations continued to expand. Visitors came to view the growing collection of paintings and statuary, and published papers and documents about Maryland history took the state’s story beyond its borders. Philanthropist George Peabody became a donor and established the historical society’s first publications fund. In the late 19th century, the state transferred government records into the historical society’s care.

The 20th-century dawns

The turn of the 20th century ushered in an era of great change. Educating students and the general public became the mission of many historical societies and women gained full membership. Among the first female members of the Maryland Historical Society were Annie Leakin Sioussat and Lucy Harwood Harrison. Both spent decades volunteering their time and services.

In 1906, the historical society launched the Maryland Historical Magazine, a journal featuring the best new work on Maryland history. The journal is currently published biannually.

The organization moved its home to 201 West Monument Street in 1919. The former residence of Baltimore philanthropist Enoch Pratt, with a state-of-the-art fireproof addition, came as a gift from Mary Washington Keyser, whose husband, H. Irvine Keyser, had been an active member of the society for 43 years.

Since its inception, the leaders of the historical society took responsibility for recent history. As their predecessors had done after the Civil War, the 20th-century leaders of the historical society acted on behalf of the federal government to compile the military records of Marylanders who served in both World Wars.

Throughout the 20th century, the growing diversity of Maryland’s population prompted a dramatic shift in the study of American history. Politics, wars, and the lives of notable men gave way to research and fascination with previously neglected fields such as women’s history, black history, and ethnic histories.

With ethnic studies becoming a major feature of American historical study, local genealogical societies sprang up across the country as researchers devoted their energies and careers to uncovering their pasts. The historical society’s renowned library collections of church and parish records, ship passenger lists, manuscripts, and the meticulously copied indexes to early wills and land tracts gave researchers missing pieces to their genealogical puzzles.

Modernization and Expansion

The historical society began expanding the Monument Street facility and added the Thomas and Hugg building in 1965, named for benefactors William and John Thomas. The new building included exhibition space, an auditorium with audio-visual equipment, work rooms, and storage space.

In 1981, the historical society added the France-Merrick Wing to the Thomas and Hugg Building, named for the Trustees of the Jacob and Annita France Foundation and Robert G. Merrick. In 2003, the historical society expanded yet again with the construction of the Beard Pavilion and the Carey Center for Maryland Life. This last expansion increased the exhibition space to nearly 23,000 square feet across 15 galleries and included the addition of a museum store and classroom space.

Moving into the Future

The Maryland Historical Society celebrated its 175th anniversary in 2019 and used the anniversary year for reflection on how far the organization had come and its direction for the future. After a survey of members and donors, the historical society’s Board of Trustees elected to rebrand the museum, library, and education programs as the Maryland Center for History and Culture.

In September 2020, the Maryland Center for History and Culture was officially introduced to the community.