What’s In a Name?

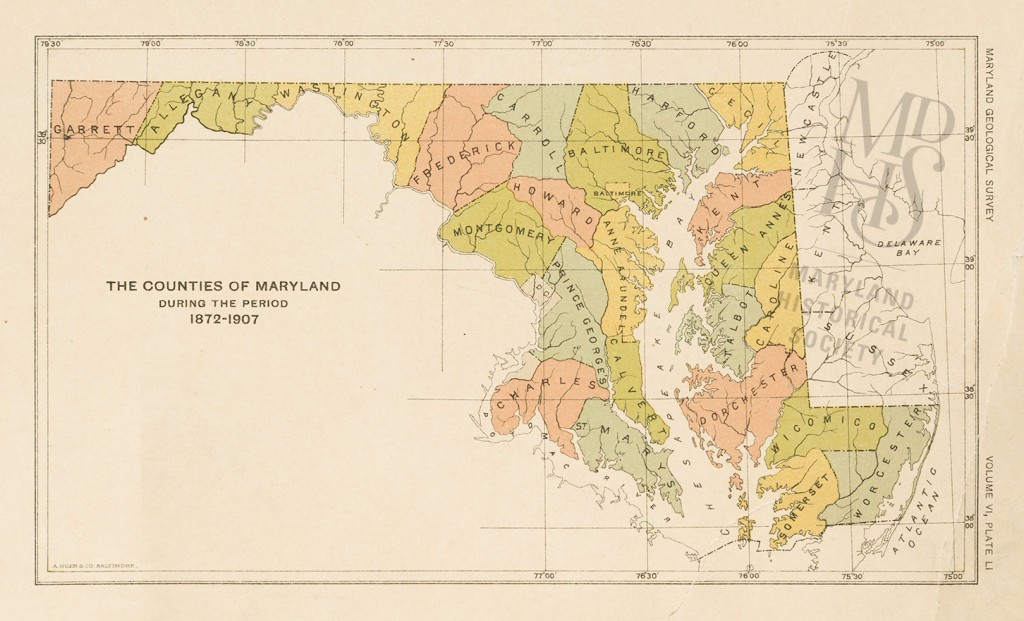

“The Counties of Maryland During the Period of 1872-1907.” A. Hoen & Co., 1908. Large Maps, Maryland, MdHS (Reference Photo).

Maryland Place Names and the Calverts

As we move about the city of Baltimore and the state of Maryland we have certain routes and places etched onto our mental map. Coming from Locust Point to the Maryland Historical Society (MdHS), I drive down streets such as Key Highway, Calvert, Paca, and Pratt. But do we ever stop and think how these streets got their names so many years ago? Do we ever think about the origin of the names of our cities and counties as well? In the Education Department at MdHS, we work with students across the 23 counties and Baltimore City, and we thought the idea of learning more about the places we live would resonate. This idea inspired one of our Homeschool Program offerings, “How Maryland Got its Names.”

MdHS Schools Programs Manager Alex Lothstein and I wanted to teach visiting students the story of Maryland’s founders through places they know and visit daily. I took a great interest in the names of the 23 counties of our state and wondered who the people were and why they merited a county in their name. The first question that needed to be asked was, what is a county?

The idea of a county, or a small administrative area that developed into what are modern-day counties, came from Europe and the island of Great Britain, where counties as we know them were originally called shires. Even today, many of the counties and electoral constituencies still have shire in their names, such as Hampshire or Yorkshire. The word county comes from the French word conté, which was a geographical area ruled by a nobleman known as a count or viscount.

As I began researching the origins of Maryland’s counties, I was given a great boost by the resources at our disposal in the H. Furlong Baldwin Library here at the MdHS. The Calvert Papers are a highlight of our collection and proved extremely helpful in our research. The collection features land grants, contracts, marriage certificates, financial statements, and other documents from many of the people for whom Maryland counties are named. I became intrigued by these people and wanted to find out more about their lives, occupations, relationships, and anything else to shed light on who they were.

The history of Maryland from the colonial perspective begins with Sir George Calvert, an English statesman in the seventeenth century who was a close adviser to King James I. Calvert was a Member of Parliament in the House of Commons, a Secretary of State, and a Privy Counsellor who would eventually have to resign his positions in 1625 after his proposed Spanish marriage for the Prince of Wales, the future Charles I, fell through. Although Calvert lost much influence in matters of state, King James raised him to Baron of Baltimore, a title in the Peerage of Ireland (his Patent of Nobility is part of the MdHS Library’s collection). Colloquially and in terms of address, the title would be referred to as “Lord” Baltimore.

After his resignation from the English government, Calvert declared himself a Roman Catholic. Whether or not he had always been Catholic in a time when being so was illegal is up for debate, but his admission was what led him to petition Charles I, James’s successor, for a charter in the New World. Named Terra Mariae, in honor of Charles’ Catholic wife from France, Henrietta Maria, the colony of Maryland, as it would be known in English, was born.

Calvert already had an interest in America as he had owned the Avalon colony in Newfoundland, and his economic ambitions were every bit as great if not more so than those of giving Catholics a place to practice their religion freely. The Calvert family not only founded the colony of Maryland, but played a big part in giving the counties their names. The most obvious among these were Calvert County, Baltimore County, and later Baltimore City, named for the peerage James I had bestowed upon Sir George and his descendants.[1] Baltimore, the town in Ireland from which comes Sir George’s title, has not only acknowledged its links to our Baltimore here in Maryland, but also named a local football club (soccer club, for us Americans) the Baltimore Crabs, a nice wink to all of us across the pond.

Sir George died just weeks after Charles I granted him the Royal Charter. His son Cecil, for whom Cecil County is named, inherited the title of Lord Baltimore as well as that of Proprietary Governor of Maryland and Newfoundland. Like his father, however, Cecil never traveled to Maryland: he sent his younger brother Leonard in his stead.

The flag of Maryland also comes from the Calverts, as it is based on the coat of arms of Lord Baltimore. The black and gold checks come from the Calvert family, while the red and white crosses come from Sir George Calvert’s mother’s family, the Crosslands.

The MdHS Library features many other valuable resources for people interested in the name origins of cities, towns, and other locales. One such gem is Hamill Kenny’s The Place Names of Maryland: Their Origin and Meaning (1984). Kenny’s book helps fill in the gaps where some debate exists as to the true origin of a county’s name. For example, Charles County is named for Charles Calvert, 3rd Lord Baltimore, not to be confused with his grandson, also Charles Calvert, who was the 5th Lord Baltimore.

Another county for which some debate exists is Frederick County. Some historians attribute the name to Frederick Calvert, 6th Lord Baltimore, but he was only 14 at the time the county was founded. Others think it was named for Frederick, Prince of Wales, who was 41 and popular in Britain, much preferred by the public to his father George II. Charles Calvert, 5th Lord Baltimore, was quite friendly with Prince Frederick and may have named his son for him. In the Calvert Papers, we have documentation from February 3, 1746, when the 5th Lord Baltimore was named Cofferer of the Household and Surveyor-General to “HRH Frederick, Prince of Wales.” The closeness of the two implies that both Frederick Calvert and the county would have been named for the father of the last King of the thirteen colonies.

The Calvert family legacy goes far beyond just the counties of Maryland, reaching our cities, streets, and even schools. The Calverts and the Lords of Baltimore were certainly not saints to be deified, but as Marylanders it is important for us to understand their legacy. While motivated by money and title, they also sought religious tolerance, which in seventeenth-century England was something valiant and rare.

Other counties in Maryland were named for more obvious sources. Washington County was, of course, named for George Washington. Montgomery County was named for a far less famous Revolutionary War general, Richard Montgomery, who led a two-pronged assault on Quebec with none other than Benedict Arnold. Howard County, meanwhile, was named for John Eager Howard. In addition to having been a great soldier and war hero, he was three times Governor of Maryland and a candidate for Vice President of the United States in 1816.

Queen Anne and Influential Women Remembered

As I began looking through the names of counties, I was struck by the number of women for whom early Maryland had baptized their counties. Seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Britain could hardly be described as a bastion of women’s rights, and in fact has always been a bit contradictory and hypocritical when it comes to women’s rights and women with great influence. As recently as 1603, just 31 years before the Ark and the Dove set forth to Maryland, England had a queen in Elizabeth I, yet women’s rights, and the rights of all regular subjects of the crown, for that matter, were quite lacking and would be for centuries. The long uphill battle for women’s rights on the island of Great Britain did not, however, stop men from naming cities, counties, and even the state of Maryland itself after women they cherished.

For instance, one of Sir George Calvert’s offspring, Grace, saw Talbot County named for her as she had married Sir Richard Talbot. Cecil Calvert’s wife, Anne Arundel, also received a county in her name.[2] Anne Arundel’s sister, Lady Mary Somerset, also joined the list of Calvert ties to have a county named for her. Mary’s husband, Henry Somerset, was raised to Marquess of Worcester, which led to that Maryland county being named thus as well.[3] Another woman to see her name grace a Maryland county was none other than Caroline Eden, wife of Sir Robert Eden and sister of Frederick Calvert, the last Lord Baltimore. Caroline County was created in 1774, at the same time Caroline’s husband was serving as the last Royal Governor of Maryland before the American Revolution.

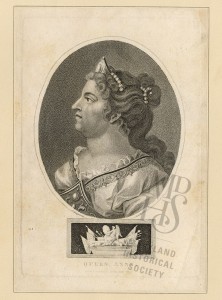

The next most obvious county named for a woman not related to the Calverts was Queen Anne. A few readers may have seen the film The Favourite in which Queen Anne is portrayed by the brilliant Olivia Colman. Queen Anne suffered from such severe gout that she was either carried or used a wheel chair for her entire reign as queen, including on her coronation day. Despite her physical agonies and her less-than-flattering portrayal in The Favourite, the reign of the last monarch of the House of Stuart was one of the most important in the history of her country. Queen Anne saw the formal unification of England and Scotland into the Kingdom of Great Britain, which would exist until 1801, when Ireland formally joined Great Britain to create the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. Therefore, while it is popular to call Queen Elizabeth II (the current monarch) the “Queen of England,” her proper title is “Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland and Head of the Commonwealth.”

Although the English Civil War, which culminated in the beheading of Charles I, had greatly reduced the monarch’s role, Anne was far from a ceremonial figurehead and was very active in politics, appointing ministers, privy counsellors, and dictating policy at home and abroad (even in the Maryland colonies). She also forged close relationships with her closest advisors and friends, including John Churchill, Duke of Marlborough, husband of the aforementioned Sarah. Marlborough’s family, the Churchills, would be influential in British politics for centuries, none more than Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill, twice Prime Minister of the United Kingdom (1940–1945 and 1951–1955). Churchill also wrote a magnificent four-part biography of his famous ancestor, the First Duke of Marlborough, for whom Upper Marlboro, Maryland, is named. Unsurprisingly, Churchill features as a name used in various places around Maryland, most notably Churchill Street in Baltimore’s Federal Hill, and a Winston Churchill High School in Montgomery County.

Anne’s husband also had a county named for him. Contrary to popular belief, Prince George’s County was not actually named for the future King George III, but rather for Prince George of Denmark, consort to Anne. Although he was no great military commander, Anne bequeathed the rank of Generalissimo to George.

Maryland’s counties certainly have interesting backstories, from the Calvert family, to Queen Anne, to more local heroes like John Eager Howard and Charles Carroll. Discussing county names was certainly the highlight of the “How Maryland Got Its Names” program, but we also used the MdHS Library resources and staff to teach the students about Maryland’s bodies of water, cities, towns, landmarks, and monuments as well. All of these resources are also at the public’s disposal: if you are ever curious about a place name, come visit us and take advantage of our wealth of materials.

(Jack Tilghman, Education Programs Assistant)

[1] Hamil Kenny, The Place Names of Maryland: Their Origin and Meaning (Baltimore: The Maryland Historical Society, 1984).