The Rise of the African Methodist Episcopal Church in Baltimore and the Bethel A.M.E. Church

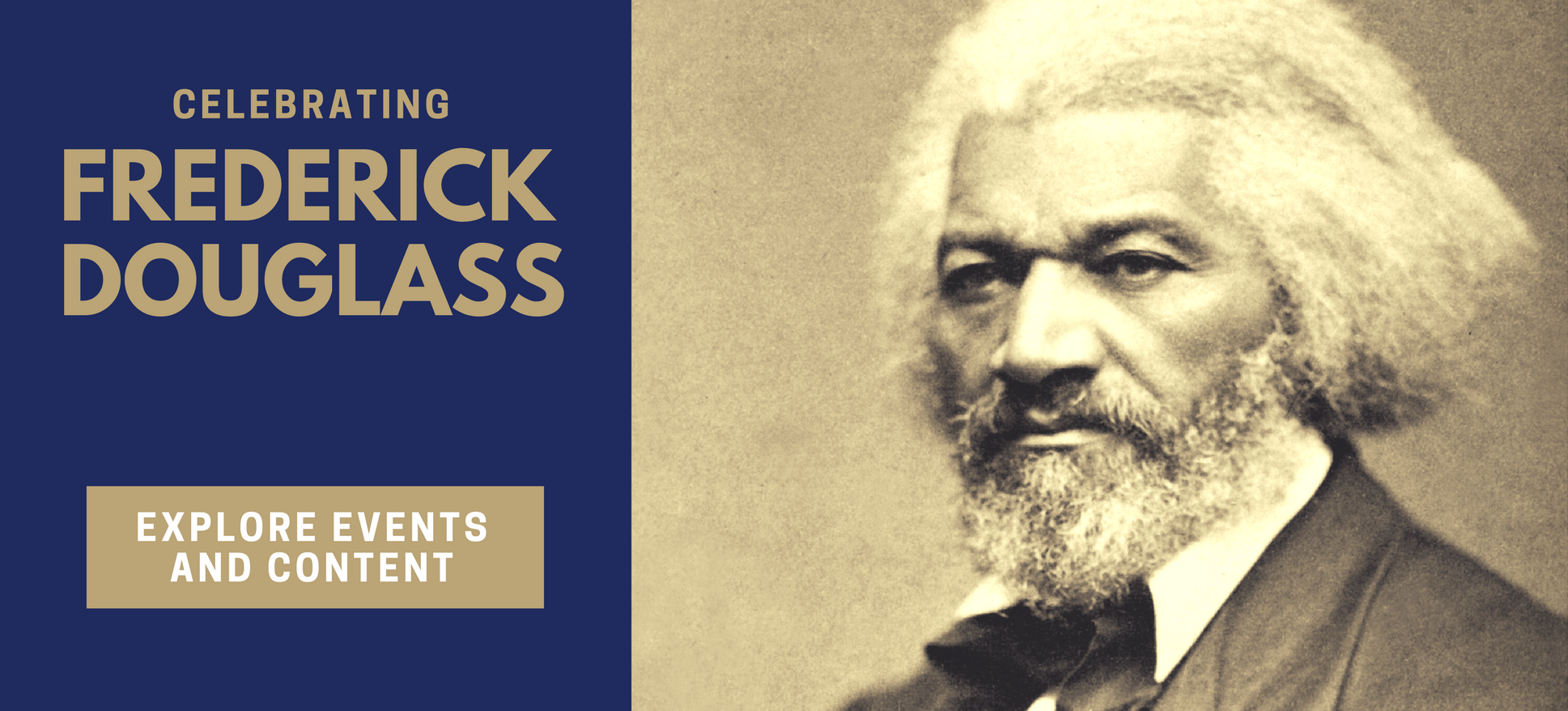

In December 1845, Reverend Darius Stokes and congregants of Bethel A.M.E. gave Robert Jefferson Breckenridge, a Presbyterian minister, a gold snuff box for his work to prevent legislation that would place restrictions on slaveholders’ ability to manumit slaves and the rights of the state’s free black population. The Presentation of a Gold Snuff Box to the Rev. R.J. Breckenridge D.D. in Bethel Church, by Rev. Darius Stokes in behalf of the colored people of Baltimore as a gift of gratitude. Dez. 18th A.D. 1845, Large Prints, [Rice 114], MdHS.

The Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church (Bethel A.M.E.) is a Baltimore landmark. It is a tribute to the city’s African American community’s fight for spiritual, as well as social and economic, equality.

Methodism was particularly popular in Maryland in its earliest years. The movement’s radical approach to preaching attracted many new congregants, black and white alike. Itinerant preachers, like Francis Ashbury, the father of the American Methodist Church, and “Black Harry” Hosier, an illiterate freedman, gave emotional and straightforward sermons which appealed to the masses. The fledgling church welcomed people of all classes, including slaves and free blacks, and preached equality amongst men. In 1764, Robert Strawbridge established the first Methodist society in America in Frederick County, Maryland. Strawberry Alley and Lovely Lane churches opened in Baltimore in the following year, and one in fourteen Baltimoreans was Methodist by 1815.

The church’s commitment to spiritual equality also encouraged African American membership. The church’s founder John Wesley was firmly anti-slavery and specifically outlawed buying and selling slaves in the tenets of the church. In 1796, a ruling was passed that all church officials must free their slaves, and laity members could only purchase slaves if they and their children would be freed at the end of a term of service. Baltimore’s early congregations were not segregated by race, and black members could be married in the church and interred in the churchyard.

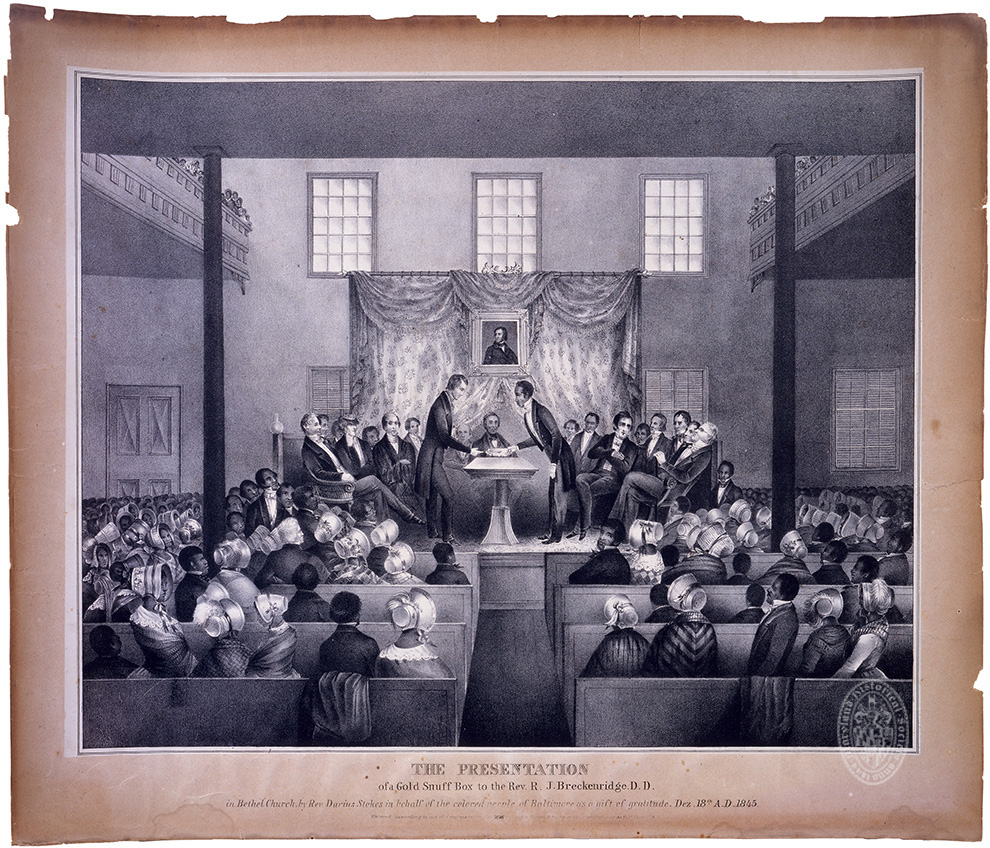

The Sharp Street Methodist Episcopal Church was Baltimore’s first black church. Sharp Street Methodist Episcopal Church, Works on Paper, MB1497, Baltimore City Life Museum Collection, MdHS.

The period of racial harmony was only temporary, and the church, particularly in the South, became more and more segregated, giving rise to the African Methodist Episcopal movement and churches like Bethel A.M.E. By the turn of the eighteenth century, black and white parishioners were no longer treated as equals in the church. African American members were forced to sit in the rear pews during services and denied burials in crowded church cemeteries. There was also concern that the African American community would demand equality in society if allowed it in church. Reverend Richard Allen (1760-1831), a former slave, became disturbed by the increasing segregation, and in 1794, he founded the country’s first independent black denomination in Philadelphia. Allen had converted to Methodism in his late teens and began preaching in parishes in the Baltimore-Philadelphia region while working to buy his freedom. By 1815, the relationship between the white and black Methodist churches had become too broken, and thus the African Methodist Episcopal Church was born.

A similar schism occurred in Baltimore–inspired by Allen’s move towards an independent black church. Several meetinghouses broke from the white-dominated churches to serve the displaced black Methodists. In 1787, the Colored Methodist Society, founded by Jacob Fortie and Caleb Hyland, separated from Lovely Lane Methodist Church. The society purchased land on Sharp Street in 1802 to build a church. The Sharp Street Methodist Church became known as the “Mother Church of African Methodism in Maryland.” However, this church was still subject to the white church authority, which some parishioners felt could not truly minister to their community.

The Bethel A.M.E. was formed to address these concerns. Coker had gained prominence in the Sharp Street church as a deacon. Ashbury had ordained Coker, a runaway slave from Frederick County, during his time in New York. He decided to return to Maryland in 1801 to preach and advocate for the end of slavery. He is credited with being the first black Marylander to publish an abolitionist’s treatise, A Dialogue between a Virginian and an African Minister.

Bethel A.M.E. moved into the vacated St. Peter’s Protestant Episcopal Church building in 1912. From George Washington Howard’s “The Monumental City, its past history and present resources,” 1873. (REFERENCE PHOTO)

Coker and others eventually withdrew from the Sharp Street Church. By May 9, 1815, Coker and his congregation officially became known as the African Methodist Bethel Society. Less than a year later, Bethel A.M.E incorporated, adopting its own constitution and becoming an independent church. The church was located on East Saratoga Street in a former Lutheran church. On April 17, 1816, the formalization of the African Methodist Episcopal Church saw members from the Strawberry Alley Meeting House group and the Colored Methodist Society join the newly organized Bethel A.M.E. church. Membership in Bethel A.M.E grew under Coker’s leadership until he resigned in 1818. His replacement, Reverend Henry Harden, saw the congregation continue to grow, and by 1853, the congregation exceeded 1,500 members. Bethel was criticized because of its lack of inclusion of enslaved parishioners, but was successful nonetheless.

Bethel became an incubator for social change, as well as spiritual improvement. The church became very influential in the African Methodist Episcopal movement with several pastors achieving bishop status. The church also attracted many community leaders to its pews. One member, George Hackett, helped prevent the re-enslavement and/or expulsion of Maryland’s free blacks after John Brown’s raid by organizing resistance to the proposed legislation. Hackett also worked with Isaac Myers and other lay members of the church to form the Chesapeake and Marine Railway and Drydock Company in 1865 in response to white ship caulkers forcing black caulkers out of the profession. The church also hosted the Moral Mental Improvement Society, a literary and debate society, and in 1865, supported the formation of the Douglass Institute. Myers also revolutionized Sunday school teaching with his practices at Bethel. These classes not only provided religious education but also taught reading and writing. His work brought Bethel to the forefront of religious education and he later hosted conferences on the subject. The late 1800s saw church members expand their aid work. Male and female members formed aid and beneficial societies, such as the Rising Star of Daniel A. Payne Lodge of the Good Samaritans and the Ladies Sewing Circle of Bethel Church. The women’s group provided food and other necessities for the city’s poor.

The church moved to Druid Hill Avenue in 1912 to the former home of St. Peter’s Protestant Episcopal Church. The Saratoga Street location was too far from its constituents, and the city had decided to widen the street in 1909. Reverend Levi Coppin had attempted to move the church in 1881 but was met with resistance from the church elders. The move was quite costly and brought financial hardship despite growing attendance. Reverend William Sampson Brooks was brought in from St. Louis to help raise the church out of debt. Even in times of economic distress, the church still fostered political and social change. In the 1920s, the church hosted Universal Negro Improvement Association events, and continued forward the work of the movers and shakers of the Civil Rights movement.

Bethel A.M.E remains a hub of Baltimore’s African American community today. Today, the church lives by the motto “Healing, Help, and Hope,” and community enrichment and spiritual guidance remain its focus.

(Sid Levy/Lara Westwood)

Sidney Levy is a volunteer in the Special Collections Department at the Maryland Historical Society.

Sources and Further Reading:

Chavis, Charles L. “Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church, Baltimore, Maryland (1785- ).” The Black Past: Remembered and Reclaimed.

Gallagher, Rachel. “Coker, Daniel (1780-1846).” The Black Past: Remembered and Reclaimed.

Hallmen, Sierra. “Sharp Street Memorial United Methodist Church.” Explore Baltimore Heritage. April 11, 2017.

Mamiya, Lawrence H. “A Social History of the Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Baltimore:The House of God and the Struggle of Freedom.” In American Congregations, 221-92. Vol. 1. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1994.

“Our History.”Bethel AME Church.

Phillips, Christopher. Freedom’s port: the African American community of Baltimore, 1790-1860. Urbana: Univ. of Illinois Press, 1997.

Pope-Levinson, Priscilla. “Allen, Richard (1760-1831).” The Black Past: Remembered and Reclaimed.