An American Tragedy

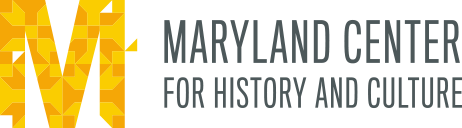

(left) Clarence Mitchell Jr. staging a one man picket line supporting school desegregation in Baltimore, 1954, MdHS, Political Ephemera Collection.

(right) Parren Mitchell protesting segregation of teacher’s training programs at Douglas High School, Paul Henderson, July 1948, MdHS, HEN.00.A2-161 (detail)

Originally posted on November 29, 2012

Many who devote their lives to bringing about social change can recall a single incident or episode that altered their perceptions and determined their path in life. Civil rights activist Rosa Parks recalls that one of the first ways she realized the difference between “a black world and a white world” was when, as a child, she saw white children riding buses to school while she had to walk. For historian Howard Zinn, featured in a previous post, it was his experiences as a bombardier during World War II that had a profound effect on his later career as a civil rights and anti-war activist, and outspoken critic of U.S. foreign policy. For brothers Clarence Mitchell Jr. (1911-1984) and Parren Mitchell (1922-2007), it was the 1933 lynching of George Armwood in the small town of Princess Anne on Maryland’s Eastern Shore that set the course for their future careers as two of Maryland’s foremost civil rights leaders.

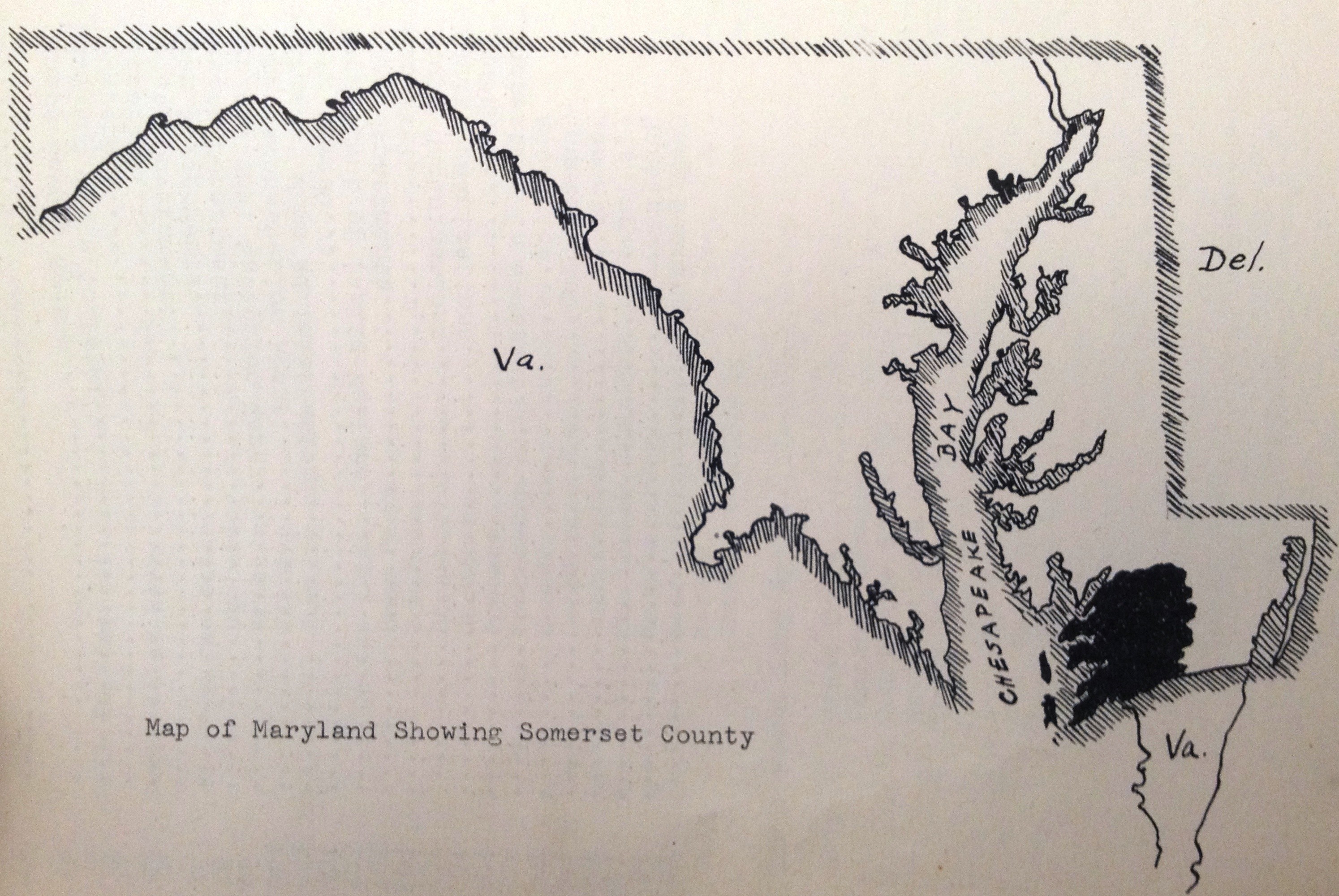

The Eastern Shore was a place apart in the 1930s. Socially and economically it was closer to the south than to the rest of Maryland, particularly in terms of race relations. The roots of a longstanding hostility between blacks and whites in the region were established early in the nation’s history. In 1783 Maryland ended the slave trade across the state, except on the Eastern Shore. Somerset County, where Princess Anne was the county seat, was one of six main centers of slave trading in the state. Isolated both geographically and economically from much of the rest of the state, the economic frustrations of poor whites in the area were often taken out on their African American neighbors. By the 1930s, the increased economic hardships of the Great Depression caused simmering hostilities to boil over, with violent result.

Map of Maryland Showing Somerset County, from Maryland’s Historic Somerset, Board of Education, Somerset County, Princess Anne, MD, 1955.

On December 4, 1931, Matthew Williams, an African American man, shot and killed his white employer in Salisbury and then turned the gun on himself in an unsuccessful suicide attempt. That evening, a mob of more than a thousand dragged Williams from his hospital bed where he lay critically wounded, and hung him up on the courthouse lawn. His body was then dragged to the town’s African American business district, and set on fire. The Williams murder was the 32nd lynching in Maryland since 1882, and the first since 1911.(1) Less than two years later, another lynching took place that would mirror the Williams murder with frightening similarity in nearby Princess Anne.

Mary Denston, the elderly wife of a Somerset County farmer, was returning to her home in Princess Anne on the morning of October 16, 1933 when she was attacked by an assailant. A manhunt quickly began for the alleged perpetrator, 22-year-old African-American George Armwood. He was soon arrested and charged with felonious assault. By 5:00 pm, an angry mob of local white residents had gathered outside the Salisbury jail where the suspect had been taken. In order to protect Armwood from the increasingly hostile crowd, state police transferred him to Baltimore. But just as quickly he was returned to Somerset county. After assuring Maryland Governor Albert Ritchie that Armwood’s safety would be guaranteed, Somerset county officials transferred Armwood to the jail house in Princess Anne, with tragic consequences.

Sources are conflicting regarding many of the details of the assault on Denston and the subsequent murder of George Armwood, but what is certain is that on the evening of October 18 a mob of a thousand or more people stormed into the Princess Anne jail house and hauled Armwood from his cell down to the street below. Before he was hung from a tree some distance away, Armwood was dragged through the streets, beaten, stabbed, and had one ear hacked off. Armwood’s lifeless body was then paraded through the town, finally ending up near the town’s courthouse, where the mob doused the corpse with gasoline and set it on fire.

Clarence Mitchell Jr. was a cub reporter for Baltimore’s Afro-American newspaper when he was sent across the bay to report on the lynching. It was his first assignment with the paper. Mitchell, accompanied by photographer Paul Henderson and two other reporters from the newspaper, arrived in Princess Anne mid morning on October 19 after an all night journey from Baltimore. By the time the four newspapermen arrived at the crime scene, Armwood had been dead for some time. Mitchell described the horrific sight in vivid detail for the readers of the October 28 issue of the Afro-American:

“The skin of George Armwood was scorched and blackened while his face had suffered many blows from sharp and heavy instruments. A cursory glance revealed that one ear was missing and his tongue clenched between his teeth, gave evidence of his great agony before death. There is no adequate description of the mute evidence of gloating on the part of whites who gathered to watch the effect upon our people.”

In a 1977 interview conducted for the McKeldin-Jackson Oral History Project, Mitchell goes into further detail about the lynching:

[soundcloud url=”http://api.soundcloud.com/tracks/68190801″ iframe=”true” /]

Interviewer Charles Wagandt can be heard expressing utter disbelief at the idea that the lynching was advertised, but in fact this was the case. Denton Watson, Mitchell’s official biographer, writes that,

“…the advent of the lynching had been well advertised throughout Maryland, neighboring Washington, D.C., and northern Virginia. In Princess Anne members of the fire department sounded the alarm and brought out the fire truck as a signal for the mob to gather. Everyone, including newspaper reporters, had ample time to attend the event. No one was surprised by the news….”

The lynching was celebrated throughout the town. The Afro-American reported that the mob danced around Armwood’s burnt remains singing “John Brown’s Body” and “Give me something to remember you by.” Small crowds gathered throughout the night discussing the murder. One man was quoted as stating, “It would have cost the state $1,000 to hang the man. It cost us 75 cents.” Pieces from the rope used to hang Armwood were taken as souvenirs.

Mitchell returned to his home on Bloom street in northwest Baltimore a changed man. He had been involved in civil rights activities prior to the lynching—in 1932 he joined the Baltimore branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and was the vice president of the City Wide Young Peoples Forum (established by future wife Juanita Jackson). But being witness to the violence of the lynching, which was outside the scope of his experiences living in Baltimore, galvanized his thinking. This, and his coverage of the trial of the Scottsboro Boys, nine African American boys charged with the rape of two white women in Scottsboro, Alabama, “awakened his interest in the…need for extensive social and judicial reforms in the country.” That evening, as he related the events of the day to his family over dinner he was so upset he couldn’t eat. For Clarence’s younger brother Parren, 11 years old at the time, seeing his brother’s reaction had a profound effect on the boy. In the clip below taken from a 1976 McKeldin-Jackson Project interview, Parren Mitchell discusses his reaction to his brother’s experience and the impact it had on him.

[soundcloud url=”http://api.soundcloud.com/tracks/68190892″ iframe=”true” /]

The murder of George Armwood was the last recorded lynching in Maryland. Clarence returned to Princess Anne to cover the trial of four men arrested for their participation in the lynching. Violence was again in the air as another mob formed, and National Guard troops were sent in. The case was eventually dismissed due to insufficient evidence. Out of the more than 5,000 documented lynchings that occurred in the United States between 1890 and 1960, less than one percent resulted in a conviction.

Clarence Mitchell, Jr. and Parren Mitchell, not dated, Clarence Mitchell Jr. Funeral Program, March 23, 1984, MdHS, MS 3092.

Both Clarence and Parren went on to dedicate their lives to furthering the cause of civil rights. Following World War II, Clarence became the labor secretary for the NAACP, and in 1950 he became the director of the organization’s Washington bureau, quickly emerging as the leading civil rights lobbyist in Washington. Known as the “101st Senator,” he was instrumental in helping to usher major civil rights legislation through Congress: The Civil Rights Acts of 1957, 1960, and 1964, the Voting Rights Act of 1965, and the Fair Housing Act of 1968. One journalist called him “the prime source of moral pressure for the cause of racial justice.” In 1985 the city courthouse in downtown Baltimore was named in his honor.

Parren’s career was no less distinguished than that of his elder brother’s. Within a year of the Armwood lynching, Parren joined his brother in a picket against local merchants over discriminatory hiring practices near their home in northwest Baltimore. Over the course of a more than 50 year career in the civil rights movement and politics at the state and national level, Mitchell established a number of firsts for African-Americans. In 1950 he became the first to attend the University of Maryland’s College Park campus when he was accepted into the school’s graduate school of sociology after suing to gain entrance.

When Mitchell was elected to Congress in 1970 as a representative of Maryland’s 7th district, he not only became the first African-American congressman from Maryland, but the first since 1898 to hold a congressional seat from a state south of the Mason-Dixon line. He also was one of the founding members of the congressional black caucus. Over the course of his eight terms as a congressman, Mitchell remained a tireless advocate for increasing economic opportunities for minorities and minority owned businesses. (Damon Talbot)

Sources and further reading:

(1) Lion in the Lobby: Clarence Mitchell, Jr.’s Struggle for the Passage of Civil Rights Laws, Denton L. Watson (New York: William Morrow and Company, Inc., 1990), p 32.

African American Leaders of Maryland: a Portrait Gallery, Suzanne E. Chapelle & Glenn O. Phillips (Baltimore: Maryland Historical Society, 2004)

“Clarence Mitchell: Man who was always there,” Peter Kumpa, Baltimore Evening Sun, March 20, 1984.

Here Lies Jim Crow: Civil Rights in Maryland, C. Fraser Smith (Baltimore: The JohnsHopkinsUniversity Press, 2008)

“Parren J. Mitchell: 1922-2007, Crusader for justice dies at 85,” Sun staff, Baltimore Sun, May 29, 2007

“Parren Mitchell, 85, Congressman and Rights Leader, Dies,” Douglas Martin, The New York Times, May 30, 2007.

“Shore starting to face up to past, some say,” Tom Dunkel, Baltimore Sun, February 25, 2007.

http://www.msa.md.gov/megafile/msa/speccol/sc3500/sc3520/013700/013750/html/13750bio.html

http://www.visionaryproject.org/mitchellparren/

http://baic.house.gov/member-profiles/profile.html?intID=60

http://suite101.com/article/rosa-parks-challenges-segregation-law-a175677